On Wireless IoT protocols

When designing an IoT device, another question you need to answer early is how are you going to connect devices to each other. Again, I will try to summarize the current (2024) most popular choices and their advantages and disadvantages in specific scenarios.

NB: This post is about wireless technologies, and is not touching 485, Ethernet, CAN, Modbus, and other typically wired thingies.

Wi-Fi aka WiFi aka Wifi

For IoT connectivity, WiFi is the first technology that comes to mind for most. WiFi SoCs are cheap, almost everything supports it, and for industrial or commercial deployments you can rely on already having or setting up wireless routers to support your devices.

However, WiFi has plenty of inherent disadvantages that prompt me to recommend looking elsewhere.

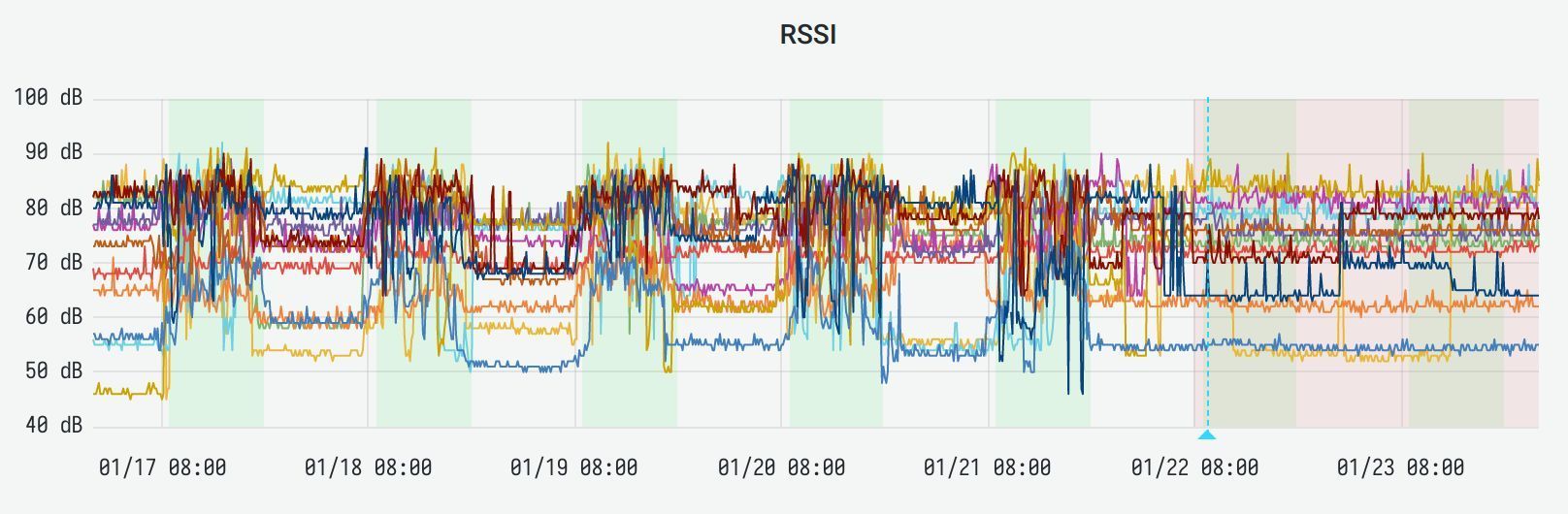

Firstly, interference. WiFi (b/g) operates on 2.4 Ghz frequency and has only 13-14 “channels” or base frequencies to choose from. So all of the mobile phones, office hotspots, WiFi from a burger joint across the street, and IoT devices themselves fight for survival in an extremely polluted spectrum. Other devices, like microwave ovens, for example, can add even more chaos. So it’s typical to see a picture like this:

(Green is 9am-7pm, chart starts on Monday and represents one week.)

When people come to work, WiFi signal gets worse by an order of magnitude, and some IoT devices can even lose network in conditions like this. Add to this some clueless admins who see “transmit power” setting and set it to max — the more power the better, right! (Not right.)

Secondly, security. Almost every wannabe (or real) evil hacker carries a WiFi hacking tool with them: their laptop. You don’t need anything else. With a laptop and a strong enough card you can: force devices to disassociate from a network, jam the channel (create a lot of interference), and in some cases (when using WPA2 Personal or lower levels of security) even capture and brute-force authentication packets, compromising the whole network.

Thirdly, penetration. The frequency of 2.4 GHz is absorbed readily by people, walls, floors, water, and pretty much everything. So effective WiFi range with typical for IoT transmit power in a commercial environment can be as low as 10 meters. Installing a router every 10 meters is probably not feasible, creates another maintenance load, and can be a(nother) security nightmare if compromised.

So altogether, WiFi is easy to start with but doesn’t scale. It’s suitable for consumer products, but for larger IoT deployments like smart sensors and meters I recommend looking elsewhere.

WiFi can be a good choice as IoT protocol if:

- you make a consumer device,

- it’s okay to push connectivity management to the users,

- devices are installed in tight groups around the routers,

- security is not No.1 concern.

“WiFi” HaLow

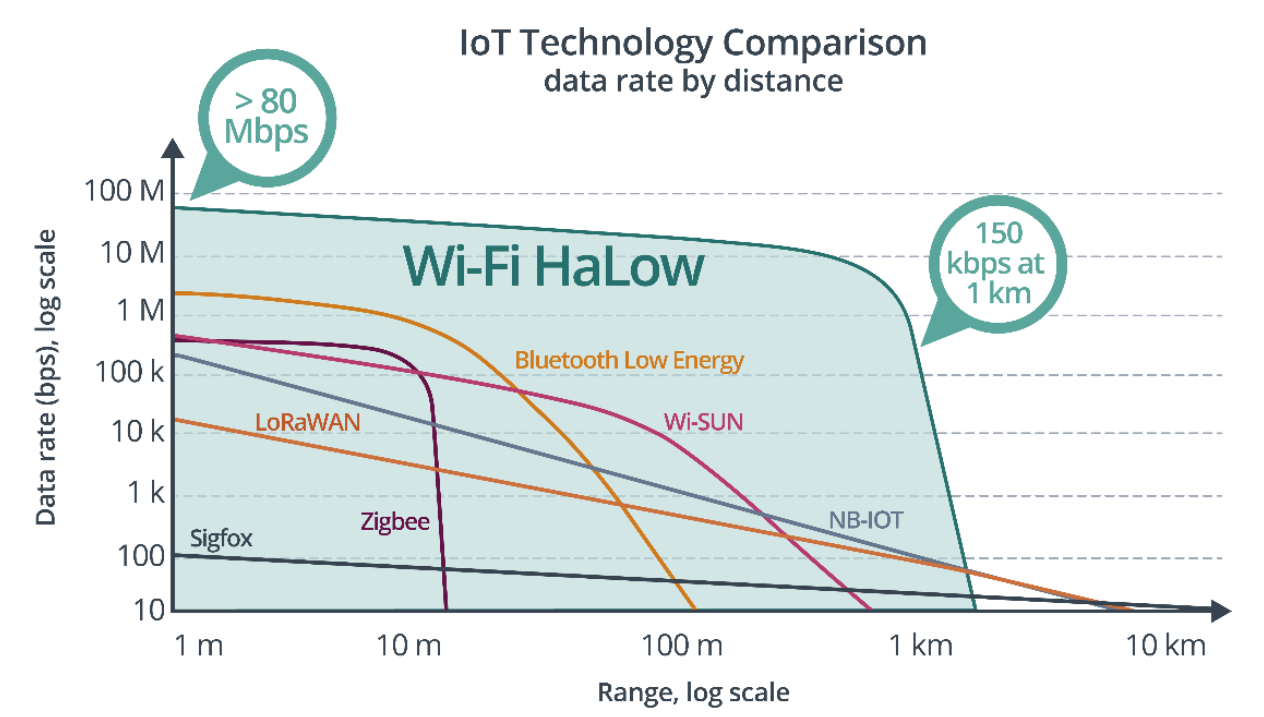

WiFi HaLow aka IEEE 802.11ah is an initiative pushed almost entirely by a single company, Silex Technology. It uses similar packet structures as “normal” WiFi, but operates in a sub-GHz spectrum of 900 MHz. It allows for much better indoor coverage and penetration while keeping a rather high bandwidth of up to 347 Mbit/s.

Why do I quote “WiFi”? Because this standard is based on WiFi but it’s NOT WiFi. It needs special routers, special wireless chips, special bridges, special everything. Effectively, they could call it Krevedko HaLow.

And herein lies the issue, there are barely 2-3 SoCs on the market, their price is high, and good luck finding an AP with HaLow support.

However, it’s worth keeping an eye on this one! Maybe in 10 years.

HaLow can be a good choice as IoT protocol if:

- you like living on the bleeding edge.

Zigbee

Another protocol from 2.4 GHz space is Zigbee by Zigbee Alliance (though some devices can operate in sub-GHz bands as well). It’s built upon IEEE 802.15.4 standard which specifies the lower protocol physical and MAC layers. Zigbee application layer defines topology and communication models. It can work in star, tree, or full mesh networks using several device types:

- Coordinator - handles the network, routing, and can interface with other Zigbee networks, each network needs one,

- Router or Relay - can bridge data between devices to extend range or form topologies,

- End Device - can only transmit data.

Zigbee networks typically use distance-vector based routing and the devices cannot move or sleep for extended periods of time, or the routing table will have to be rebuilt. So it only works for constantly powered devices that disconnect rarely.

Maximum payload size in Zigbee is 73-100 bytes, depending on security and routing settings, so it’s not suitable for larger messages or, for example, transmitting a firmware OTA.

The main footgun that Zigbee shoots itself in the foot is price. Zigbee Alliance requires certification for all devices, so the price of SoCs and modules with Zigbee support can be 5-10 times higher than other wireless technologies.

ZigBee can be a good choice as IoT protocol if:

- price is not an issue,

- messages are tiny,

- devices must interoperate with some existing ZigBee technology.

LoRa & LoRaWAN

LOng RAnge or LoRa is a standard developed (currently) by Semtech, based in California. It’s typically using sub-GHz frequencies (thus “long range”), but modules exist that work in 2.4 GHz bands as well, mostly for indoor applications.

LoRa is using chirp spread spectrum (CSS) modulation, which is basically spreading the sinusoidal signal over the whole allocated channel, making it very resistant to noise and interference, at a cost of much lower bandwidth.

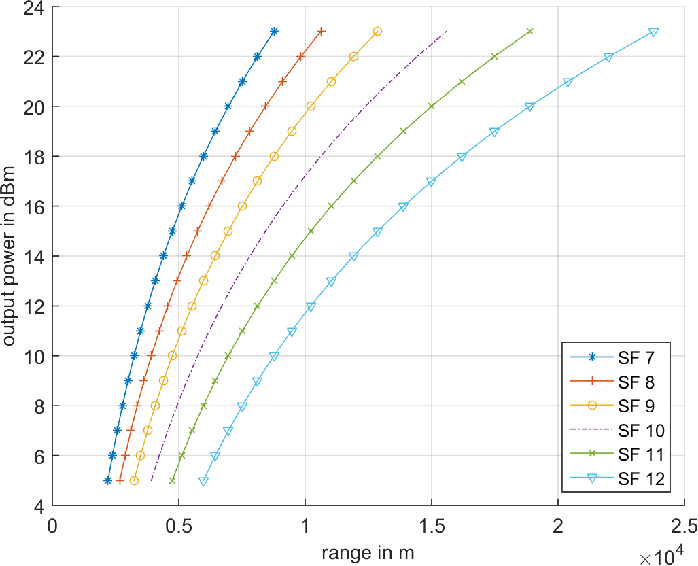

Typical LoRa modules use transmit power of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and then up to 1, 2, or even more Watts. 500 mW are most common, and in an urban environment, the range can be as good as 500-1000 meters.

LoRa bandwidth can be adjusted using the so-called Spread Factor (SF) - the count of chirps per bit of transfer. It typically ranges from 7 (128 chirps per bit) to 12 (4096 chirps per bit). On SF7 the throughput per channel is ~10 kbps, on SF12 it’s as low at 0.15 kbps (kiloBIT, i.e. 0.15 kbps is barely 18 bytes per second).

Another factor for LoRa is regulatory. Some countries limit the duty cycle of LoRa devices to 10% or even 1%, making effective bandwidth per device 10x or 100x less. It is also necessary to pick correct frequency bands for different countries, so if your project is global, that can quickly get daunting.

LoRa is more suitable for very small and infrequent data packets that need to be sent over greater distances. The payload size on SF12 is also limited to just 51 bytes.

With many devices broadcasting at the same time, it’s also important to manage network slotting, otherwise for the gateway device it is impossible to tell apart the signals, and if one device sends “hello!” and another “wassup” at the exact same moment, the gateway will receive “hwealslsou!p” or something like that. A higher-level protocol called LoRaWAN is used to combat that.

LoRaWAN is supposed to orchestrate devices’ frequencies, data rate, power modes, and addressing / routing to be able to connect them to “WAN” (in a broad sense — it can be Internet or it can be a local network of a LoRaWAN gateway).

LoRaWAN topology is tree-like — called by the standard “a star of stars” (that certainly has the ring!) It defines 3 “classes” of devices:

- Class A — ALOHA-type protocol for low-power devices, the device initiates data exchange, optionally followed by a short downlink window (for sending commands, etc.) The Gateway must manage the buffering of downlink data for Class A devices,

- Class B — same as Class A, but waking up at a periodic interval with a TCP-like keepalive pinging model,

- Class C — always-online, half-duplex devices that typically operate on a stationary power source.

Since the Gateway is managing devices’ modes, routing, and power, it’s typically faster than “raw” LoRa. Medium-size LoRaWAN installations can achieve real-life speeds of 10-30 kbps.

It’s worth mentioning that in many larger cities in Europe, US, and China, Internet-connected LoRaWAN is offered as a service by multiple service providers. ThingsNetwork is a free and “open-source” one, giving some very limited connectivity for devices that rarely exchange information. Tencent LPWAN is another example that I know of, commercially available in most T-1 cities in China.

LoRaWAN can be a good choice as IoT protocol if:

- devices communicate very small amounts of data,

- downlink (“command”) latency is not important,

- it’s okay to bear all the operational load of managing the Gateways or pay for commercial.

Thread & other IEEE 802.15.4

IEEE 802.15.4 standard is the basis for many other protocols except Zigbee: WirelessHART, SNAP, 6LoWPAN, MiWi, and Thread. Thread stands out among them as an active standard with some weighty members on the committee: ARM, Google Nest, Apple, OSRAM, Samsung, NXP, Qualcomm. Google has also released an BSD-licensed open-source implementation called OpenThread.

Based on 6LoWPAN (which is based on IEEE 802.15.4), Thread uses IPv6 addressing and requires a special Border Router device (typically running some POSIX OS e.g. Linux) that implements routing and uplink / downlink connection for the network. It supports self-healing automatic building of mesh networks with mixed topologies.

For all purposes, Thread Border Router acts as a gateway connecting your devices upstream to the Internet or other networks and handles sending and receiving of messages. Within the Thread network devices have access to UDP layer (and a protocol on top of it, like CoAP or MQTT-SN), DNSv6, and general IPv4 access via NAT64 on the Border Router.

Thread packets are transferred over UDP and limited to 1280 bytes without fragmentation, or 2047 bytes (payload 1999 bytes) with fragmentation. There’s an ongoing development of supporting CoAP(s) block-wise transfer for larger payloads, but this may or may not work with different builds. One to keep an eye on!

Security in Thread supports full message encryption and secure provisioning of devices with our without human intervention. In larger networks, CCM-based joining is used, operating using Thread Domain name, unique device identifiers, and certificates that have to be issued by a trust anchor of the network.

Thread works on any frequency supported by IEEE 802.15.4 standard, i.e. it can work on 2.4 GHz using Bluetooth channels, or sub-GHz on supporting SoCs. The most typically used SoCs for Thread are Nordic nRF5x family (2.4 GHz) or TI CC2652 (sub-GHz).

Thread can be a great choice as IoT protocol if:

- the payloads are not too large (under 2 KB),

- managing Border Routers is operationally feasible.

Bluetooth & BLE

Bluetooth Mesh is a full-stack protocol on top of Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) that defines everything from the low-level physical radio layer to high-level application layer. It operates on Bluetooth frequencies in 2.4 GHz band, so it shares some of the deficiencies with WiFi other 2.4 GHz protocols. However, Bluetooth also uses some smart tricks like frequency hopping and retransmits to quite effectively combat interference.

Routing in BLE Mesh is based on flood: every node retransmits a message further down the mesh until some specific number of transmits (hops) is reached. Typically this is limited to 2 or 5, but the highest limit defined by the standard is 127.

Message payload can be up to 384 bytes (using fragmentation), with a single segment being just 11 bytes. It’s best to keep the messages no longer than one segment, of course, to prevent excessive packet loss and traffic spikes.

In BLE Mesh, every device assumes some of these roles:

- Relay — can receive and retransmit mesh messages,

- Proxy — can also receive and retransmit mesh messages originating from outside the network, e.g. from Bluetooth-enabled phones or other devices,

- Low Power — typically operates on battery on low duty cycles,

- Friend (sic!) — can cache messages for Low Power nodes to be delivered when Low Power node wakes up.

BLE Mesh operates on top of Bluetooth Models which define software implementations of certain behaviors. Some of the Models are mandatory, and some are optional or user-configurable.

Here is a definition of Model from BLE docs:

“…defines a set of States, State Transitions, State Bindings, Messages, and other associated behaviors. An Element within a Node must support one or more models, and it is the model or models that define the functionality that an Element has. There is a number of models that are defined by the Bluetooth SIG, and many of them are deliberately positioned as “generic” models, having potential utility within a wide range of device types.”

Two mandatory Models are Configuration and Health Servers, which are used to configure the device and query device health. Those are typically implemented in the BLE SoC firmware and just need to be enabled by the developer.

Other models are:

- OnOff — implementing a simple switch or a relay,

- Level — implementing a numeric value like temperature,

- Transition Time — implementing interval-based changes of state, typically for Level Models (e.g. dimming of light),

- Power OnOff — implementing an OnOff Model after device powers up,

- Power Level — same, but for Level Model,

- Battery — implementing battery status,

- Location — implementing location-based services,

- Manufacturer, User, and Admin properties — generic properties that do not fit in other categories.

BLE Mesh also defines extensive models for Lighting, Sensors, and Scheduling.

Hardware that supports BLE Mesh is numerous. Most SoCs that support Bluetooth are also certified for Mesh: nRF5, Qualcomm, Marvell, ST Micro, Espressif, AliOS SoCs, and many more. Another great implementation is Linux Foundation backed Zephyr OS https://www.zephyrproject.org/

Perhaps what can be more interesting is that there are some pure software implementations of BLE Mesh. Most notable are Apache NimBLE and Bluez. The latter runs on any Linux distro that supports BLE hardware, and can give you capabilities to extend your BLE Mesh with powerful devices. As of early 2022, not everything is working in Bluez, but it’s definitely one to watch!

BLE Mesh can be a good choice for an IoT project that:

- operates within conceptual bounds of BLE Mesh (especially, lighting control and simple sensing),

- does not need large payloads over 200-300 bytes,

- has decent device installation density, as BLE range is typically within 10-20 m,

- does not need an Internet uplink or open to operating a custom border device.

433 MHz GFSK

On the other end of the spectrum (pun intended!) from fully managed protocols like BLE Mesh or Thread is a raw radio over unlicensed sub-GHz bands. One of the “best” bands which have a lot of hardware and software readily made is 433 MHz or ISM (industrial, scientific and medical) radio band (concrete frequency depends on the ITU region).

If your payload requirements are low, range requirements are high, and the cost is important, going raw radio is one possible route. Some of the cheapest modules are HC-12, based on SI4463 IC, or transceivers based on CC1101.

Most of these modules offer exceptional sensitivity up to -120-130 dBm (compare with WiFi modules which are -90 dBm at best, every 6 dBm is double the range, so e.g. -126 dBm is 64x the range of WiFi), up to 100 channels, and typically work using GFSK modulation.

FSK uses frequency shifts to encode bits, GFSK adds Gaussian smoothing to the shifts, making it easier to decode bits on the receiving side.

Most of these modules are also very easy to work with, as they present UART TTL interface. Put two nearby, write “Hello” to one’s Serial TX pin, read “Hello” from another’s Serial RX pin.

With a 100% duty cycle (which might be illegal in some countries, do your research!), the throughput of GFSK-modulated 433 MHz transceiver is from 5 to 200 kbps (NB: lowercase “b” aka “bits”). Lower rates allow for more sensitivity, at the maximum rate of 236 kbps the total link budget is about -100 dBm.

Of course, raw means you need to take care of channel negotiation, interference management, duty cycles, duplex transfer windows, encryption, decryption, fragmentation, reassembly, routing, etc, etc all by yourself. But for moderately savvy tech teams this can open a lot of possibilities that are not open when using off-the-shelf protocols.

So raw radio can be a good choice if:

- range is important, or installation density is unpredictable,

- low price is important,

- payloads are small,

- developers are ready to tackle some interesting challenges.

2/3/4G & LTE

All aforementioned protocols assume that devices either do not need an Internet connection, or are connected via some kind of router / gateway. It greatly increases the operational burden on your project, and in some scenarios can be even impossible.

Cellular modules can be used then to connect every device to the Internet using the same network infrastructure that exists everywhere for cell phones. These modules typically require a SIM card or an eSIM IC module, and a subscription from a network provider. Global IoT SIM cards exist to provide operator-independent traffic, but this can be expensive.

Cellular modules are usually constantly powered and are rather large and expensive, so they make sense in projects where Internet connectivity is important and infrastructure is not managed.

Some of the bigger module providers are Quectel, Huawei, Qualcomm (Sierra Wireless), Simcom. Most of these modules will provide some kind of AT-command based factory firmware and / or a PPP interface. Unfortunately, there is no single standard for AT-commands, so to open a TCP socket some modules might use AT+QIOPEN and some AT+SDATACONF followed by AT+SDATASTART, and others something else completely. So these modules are not interchangeable.

The price of the modules can be a limiting factor. 2G modules are the cheapest ($3-5), but 2G is either already removed or being sunset in most countries. 3G is more expensive, 4G is more expensive still ($10 easily), and LTE and 5G modules can cost upward of a hundred USD.

Operator subscription is another cost, this time ongoing. The traffic can be rather expensive. For example, Hologram, one of the bigger global SIM providers, charges $5 for the card and $0.75 device per month plus $0.34 per MB of data.

Another issue is coverage. For projects that are installed indoors, good antennas need to be designed. Modern cellphones are basically whole case antennas, and some IoT devices can get pretty bulky if a similar signal noise floor is needed. Some deep indoor or basement rooms might not have coverage at all and require wired external antennas.

But, of course, the freedom and flexibility of each device connected to the Internet separately can override all of these concerns.

So a cellular 2/3/4G modem can be a good choice for an IoT project if:

- price is not an issue,

- business model covers ongoing costs,

- devices do not have to be miniature,

- installation is outdoors or not too deep indoors.

NB-IoT & LTE Cat.1

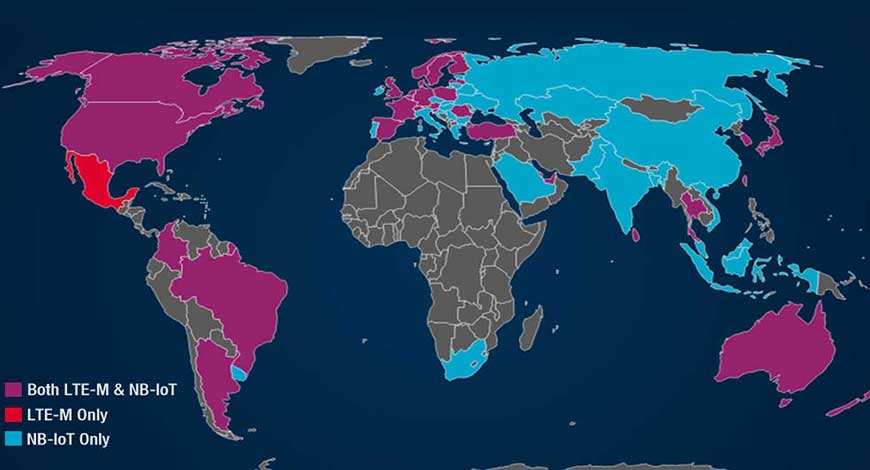

Since most of the IoT use cases for cellular-connected devices are just sending some data once in a while, network operators and 3GPP group started working on specialized cellular protocols that do not need to support voice and high-speed data transfers. Thus NB-IoT standard was born.

NB-IoT, for the most part, reuses the same infrastructure as now deprecated 2G, so the operators who invested billions of dollars into 2G towers do not need to throw it all away. Minor, mostly software upgrades make it possible for old 2G towers to support NB-IoT, making it very lucrative for the operators.

Since 2G and thus NB-IoT work in sub-GHz bands (typically), the coverage is greatly extended at the cost of throughput. Maximum speed for NB-IoT is about 250 kbps up/down, but in real scenarios, it is much smaller. The gains in coverage are on 6-9 dBm scale, i.e. about 2-3x the range of 4G. NB-IoT can also work inside LTE bands, but this usage is not very widespread.

NB-IoT networks do not support voice calls, SMS, and fast cell handover, so it’s not suitable for moving devices like vehicular IoT. However, for stationary devices, this is not an issue.

NB-IoT modules are usually much cheaper than 4G modules (around $3-5), and many come with pre-configured operator SIM cards that are prepaid for up to 10 years. However, the amount of traffic on these cards can be very low, around 300 MB per year is pretty normal. In PRC, China Mobile offers these 10-year cards at about $15.

A single NB-IoT tower can theoretically support 200,000 and more devices (typical 4G tower can serve about 400 connections). This is achieved via network-enforced “discontinuous reception”.

The modules can enter eDRX (Extended Discontinuous Reception) or PSM (Power Save Mode) modes that signal to the tower to buffer some data for them. eDRX is set up with a configurable sleep timeout which is ranging from 20.48 sec to ~3 hours (10485.76 sec). During sleep, the operator “should” (this varies from op to op) buffer some data for the device. Once the device comes up, the data is delivered.

If your device only sends data uplink, it is not an issue at all. For downlink it is a bit more complicated. Not every network protocol can survive discontinuous reception. If you use MQTT, make sure to configure correct keep-alive intervals so the broker will not mark your device as offline too early.

UDP-based protocols like CoAP or LwM2M can be a better choice for NB-IoT devices, if all other constraints are met. UDP data should also be buffered by the operator. You can check my other post to learn about the pros and cons of this approach.

Since during eDRX or PSM the radio is effectively off, NB-IoT modules consume much less energy than 3/4G modules, making them suitable for carefully planned battery-powered applications.

NB-IoT is very well adopted in some countries, but there are some countries like Mexico, Australia, to some extent North American countries, that adopted a competing standard called LTE-M.

For IoT purposes, we are more interested in LTE-M Cat.1, the slower and more suitable substandard. Its main differences from NB-IoT are speed and power-saving features.

Cat.1 is much faster and supports voice and real-time TCP-style network communication. It reuses existing LTE infrastructure, so it’s much more similar to conventional 4G, with all the problems that this entails: more expensive modules, much weaker indoor coverage, and costly SIM cards.

NB-IoT is a great fit for any IoT project where:

- moderate cost of the modules is okay,

- some data latency is acceptable,

- data can fit in limited traffic constraints of ~300 MB per year.

To summarize, WiFi is usually the simplest choice if the product is managed by the end user. Thread or BLE Mesh is interesting for massive deployments of low-cost devices that do not exchange much data. For sprawling outdoor deployments like farms or forests, LoRa or raw GFSK radios can be suitable. NB-IoT is the most versatile if deployments are in urban zones either indoors or outdoors.

Hope this information was helpful.

As always, if you want me to help out in choosing a protocol, or have any questions, do not hesitate to reach out at michael [at] sayap.in.